Director Danny Boyle returns from the success of Slumdog Millionaire with a vibrant depiction of man versus nature.

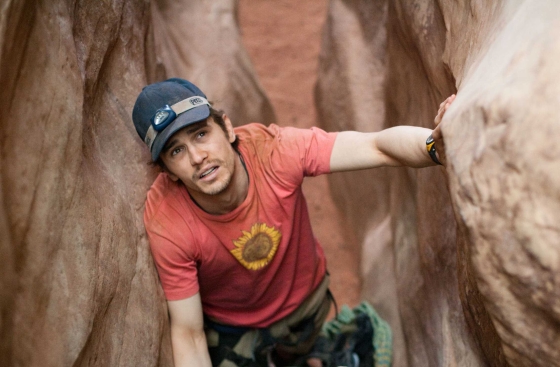

The story here is of Aaron Ralston (played by James Franco), the outdoor enthusiast who in 2003 was stranded under a boulder after falling into a remote canyon in Utah.

Beginning with an extended opening section, Boyle uses a variety of techniques (including split screen, weird angles, quick edits) to express Ralston’s energetic lifestyle as he ventures into a situation that would become ominously static.

He meets two women (Kate Mara and Amber Tamblyn) before parting with them and climbing across an isolated canyon where he becomes trapped for the next 127 hours (look out for a killer title card).

Although it was a widely publicised news story at the time, there is a dilemma when discussing the events of this film.

Although it was a widely publicised news story at the time, there is a dilemma when discussing the events of this film.

Some will go in knowing what happened, whilst others will not.

For the benefit of the latter, I’ll refrain from revealing the full details but it is worth noting that the film is not a gory exploration of Ralston’s distress and audiences might be surprised at the overall tone of the film, which is far from gloomy.

An unusual project, in that so much of it revolves around a central location, Boyle contrasts the vital specifics of Ralston’s confinement in the canyon with his interior thoughts as it becomes an increasingly desperate experience.

The details of the situation are expertly realised as a penknife, water bottle, climbing rope and digital camera all assume a vital importance with a large chunk of the film feeling like an existential prison drama.

This gives it a slightly unusual vibe, as the audience is effectively trapped with Ralston in a claustrophobic way.

Using two cinematographers (Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chedia) working in tandem, the ordeal is powerfully realised using a bag of visual tricks to delve deep into his physical and emotional trauma.

Before we get to the canyon, the sun filled landscapes of Utah are shot and edited with a vibrancy and panache recalling some of Boyle’s earlier work, notably Trainspotting and Slumdog Millionaire.

There are also some poetic details that enrich the atmosphere: the distant planes above cutting through the blue sky, insects nonchalantly roaming free and the colour of the rocks themselves which look startling in the sunlight.

Once he actually becomes trapped, a variety of different shots and perspectives help give the situation different visual flavours: the interior of his water bottle, the bone inside his arm and video diary footage on his personal camera, become important in breaking up the gruelling monotony of his predicament.

His interior thoughts are brought to life with memories, flashbacks and hallucinations: a break-up with a girlfriend (Clemence Poesy); visions of his family and childhood; a strange chat-show monologue with himself and a flash flood.

There are times when it feels the filmmakers are over-compensating for the limitations they chose, and more doses of stillness would have been welcome, but overall the visual and audio design helps us get inside Ralston’s physical and emotional situation with clarity and empathy.

But the most brilliant decision of all was the casting of James Franco. His surface charms and hidden depths as an actor provide a perfect fit for the role, as he impressively navigates the emotional ride of his character.

With an unusual amount of screen time he hits all the notes required: exuberant daring as he cycles across Utah; determined ingenuity as he tries to escape the canyon; and the desperate, haunted pain as he stares into the face of death.

A.R. Rahman’s score is a bit looser than his work on Slumdog Millionaire, but it makes for an emotional backdrop to the events on screen and Boyle’s use of songs (notably Free Blood’s ‘Never Hear Surf Music Again’) is effective in cutting together with the images on screen.

Although 127 Hours feels longer than its 93 minute running time (well, it wouldn’t it?), this is actually a sign that Boyle’s gamble in dramatising this material has actually worked.

It is an unusual project in all sorts of ways, eschewing narrative conventions and revelling in its creative rough edges, as it focuses relentlessly on one man’s physical and mental struggle.

There is something in Ralston’s struggle that is both primal and fascinating. Inevitably we ask what we ourselves would have done in the same situation.

But this film version is not just a technical exercise in outdoor survival. It is a reminder of the basic need to survive in the darkest of circumstances.

By the end 127 Hours becomes a transcendent film about the power of life in the face of death.

127 Hours closed the LFF last night and goes on US release on Friday 5th November and in the UK on Friday 7th January.

> 127 Hours at the LFF

> Official website

> Reviews from Telluride and TIFF via MUBi